History of Finnish attitudes towards large carnivores

The significance of history is in no way unimportant in the formation of attitudes towards large carnivores, even though the history harked-upon in the current discourse only extends back a little over a century to the "great wolf years", especially the child killings in south-western Finland in 1880–1881. This is fairly understandable, as the late 19th century saw the rise of the newspaper and periodical press industries in our country and accounts older than that are much harder to come by. At the same time, the most enthusiastic hunters were organising more closely and local hunters' associations were founded at an increasing rate. One of the most important duties of these associations was game management, which at the time basically meant getting rid of all predators as efficiently as possible. The development and better availability of hunting weapons and improved transportation routes also facilitated this determined and successful persecution of predators. Even though the late 19th century was an eventful time in this respect, there are many indications that large carnivores have been on people's minds long before then.

Agriculture and Christianity changed our relationship with nature

During the time of hunter-gatherers, the wilderness was where people lived and nature was worshipped. As people settled down and began farming the land, nature split into two: there were the farmed, tamed lands, and then there was the wilderness, which was perceived as a threat. It was during this time that predators began to be seen as pests that preyed on livestock. As part of the tradition known as karhunpeijaiset, a celebration held in the bear's honour after a bear hunt, a hunter would take the bear's nose, ears and eyes to obtain its power and soul. Later this same ritual was performed to take away the bear's sense of smell, hearing and sight so that it could not hurt livestock.

As Christianity spread to Finland, the new beliefs and the old pagan beliefs coexisted for centuries, during which time the church was actively trying to root out the old rites and rituals. The worshipped beasts were seen as messengers of the Devil and they were symbolically subjugated to the power of God and the church – even the bear hide, which was given the seat of honour in karhunpeijaiset, was now placed on the floor of the church for priests to walk on. The attitudes that clergymen had towards predators had a great influence on the opinions of the populace, as all hunting laws and statutes were declared to the illiterate masses directly from the pulpits.

Clear division into good and bad animals

As people's relationship with nature changed, animals began to be categorised based on their known or perceived usefulness or harmfulness. The case of the large carnivores was very clear. The legislators of Sweden–Finland had already deemed the bear and the wolf to be harmful animals in the first common law of the land in 1347. The lynx and the wolverine were relegated to the same caste in legislation introduced in the 17th and 18th centuries. The central concept in these laws was always the same: to paraphrase the text of the common law, the mentioned predators "could be killed freely by anyone, anywhere". If hunting actual game was the prerogative of the king, predators could be killed by anyone without fear of punishment. The persecution of wolves was even made a civic duty by law.

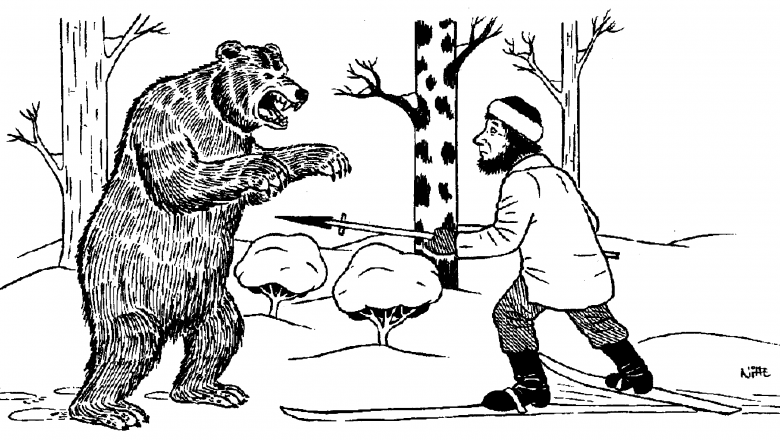

In addition to old law texts, there are other sources describing the people's attitudes towards predators. In his work The History of the Northern Peoples (1555), Olaus Magnus, a cartographer, historian and the last Catholic archbishop of Sweden, wrote down what he had heard among the people. In the book the wolverine is depicted as an insatiable glutton. The bear is given the reputation of an angry and mischievous animal. The wolf is shown as a wild and bloodthirsty beast that would rip a baby from his mother's arms any chance it got. Olaus Magnus also talks about "the war against wolves", as do many later game wardens. Magnus considered the lynx to be a fur animal, and had nothing derogatory to say about its habits or character.

Bounties were issued to fuel the persecution

A systematic war has been waged against harmful animals in Finland at least since the 14th century that continues in some ways even today. Exactly 300 years after the drafting of the first common law, the Royal Decree on Hunting, issued in 1647, introduced bounties for killing bears and wolves. Bounties for killing wolverines and lynxes were not issued until the hunting decree of 1868. The bounties for killing each of the four large carnivores were made comparable in the Imperial Hunting Decree of 1898. The infamy of each species weighed heavily on the size of the bounty. The wolf was considered to be the most dangerous animal, and for killing an adult the hunter was awarded 100 marks. For killing a pup the bounty was 50 marks. An adult wolverine was deemed to be worth as much as a wolf pup and a wolverine cub was worth 25 marks. The bear and the lynx were also considered to be worthy of only 25 marks each, regardless of age. The hunter would collect the bounty from the crown's representative by presenting the entire pelt of the killed animal. Before the pelt was given the back to the hunter, the officials made three visible, triangular holes between the pelt's ears to signify that the bounty had been paid.

The justifications behind the persecution of these pest species were primarily economic. Back then large carnivores posed a real danger to livestock and reindeer farming. In Finland cattle was allowed to graze freely in the woods in the 18th and 19th centuries, which left them particularly vulnerable to attacks. The practice of grazing in the woods survived long into the 1960s. Large carnivores were also seen as enemies of game species, and killing the predators was perceived as a way to indirect financial gain. The thinking regarding the conservation of game species was straightforward: as the number of predators dwindles, the numbers of other game animals rise, leaving more animals for the people to hunt and profit from. Wolves were also considered to be dangerous, especially to children. Even though actual human casualties were very rare in Finland, they did occur and the fear created by these incidents should not be downplayed.

The heyday of the Finnish bounty system can be placed between the Imperial Hunting Decree of 1898 and the Finnish Civil War of 1918. The factors that lead to the system's creation were probably numerous, and the aggravated hatred of predators caused by the killings of children in Southwest Finland was probably not the least of them. The bounties had an impact on the dwindling of our large carnivore populations and on limiting their geographical distribution to the eastern and northern parts of the country. The bounties began to lose their significance as the Finnish mark decreased in value from 1916 to the beginning of Finland's independence in 1917. It was no longer worth the time and effort to hunt the now rare predators using expensive ammunition. As the 20th century progressed, the world changed and the once persecuted large carnivores began to be viewed as species with small populations that needed protection. Finally, the Finnish bounty system was put to rest and no new funds have been allocated to bounties since 1975.

Sakari Mykrä & Mari Pohja-Mykrä