Many Finns share the opinion that large carnivores are an integral part of Finnish nature and important in terms of biodiversity. People also believe that large carnivores promote tourism, because they enhance

the feeling of rugged wilderness in our forests, which is something international nature tourists may be looking for.

Some critical comments were linked to the idea that decision-making has shifted too far away from local communities, with decisions being made at the national or European Union level. Many people would like to retain decision-making power in matters related to hunting large carnivores.

Bear

The Finnish brown bear population was nearly completely decimated in the late 19th century. With systematic management the population has been successfully revived. The bear has once again spread to the entire country, which has also caused concern.

During the preparation of the current bear population management plan, a research survey was conducted on Finnish attitudes toward the bear. The citizens' responses clearly indicate that the bear is a valued part of Finnish nature. However, some comments also contained fears about the bear and concerns over bear damages. The bear causes damages to reindeer, domestic animals and beekeeping, for example. A functional compensation system, the prevention of damages and maintaining a shy population that steers clear of people were considered important by the respondents.

Bears moving near populated areas cause the most fear, as they are believed to be a threat to the health and even lives of the local people. Distributing factual bear information and keeping the bears shy were considered the best ways to curb these fears.

Most respondents wanted to continue the practice of permit-based bear hunting, which was seen as the best way to maintain a bear population that steers clear of people. Most representatives of nature conservation organisations were only in favour of hunting bears that caused problems.

A majority of the respondents considered the current size of the Finnish bear population to be at an appropriate level. Practitioners of agriculture and forestry and people living in areas with the densest bear population wished for fewer bears. Environmental authorities and the representatives of nature conservation organisations were in favour of increasing the number of bears. Monitoring and research were considered to be significant factors in bear population management.

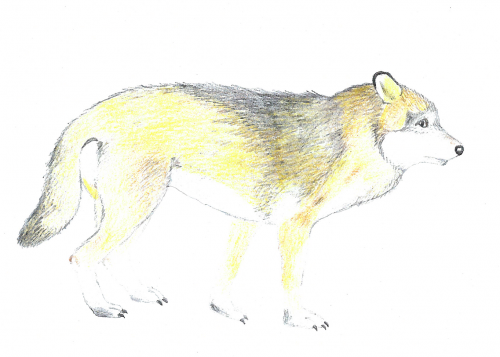

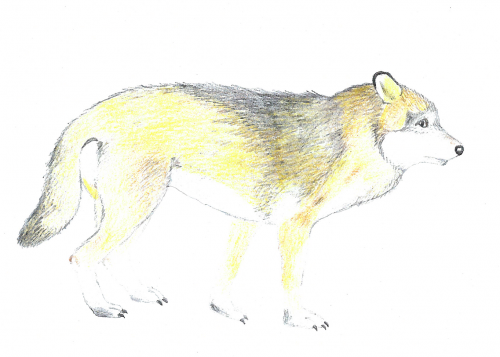

Wolf

The Finnish wolf population was quite numerous up until the 1880s, after which it was almost hunted to extinction. In recent years the growing wolf population, positive development of birth rates and the spreading of the wolf to the entire country have brought forth conflicting views on the wolf and what the goals of wolf population management should be. The discussion has been marked by negative connotations especially in eastern Finland, where the wolf population is the most numerous and growing most rapidly.

Overall, the research survey conducted as part of the preparation of the wolf population management yielded results that were negative in tone. The responses were laced with wolf fears, which were interpreted to primarily stem from the suspected lethal wolf attacks of the 19th century and the fables and stories where the wolf is depicted as a man-eater. The fear of the wolf was much stronger in western and southern Finland than in northern or eastern Finland.

The wolf was perceived to cause damages to reindeer, cattle, sheep and hunting dogs. In addition to the actual damages, negative feelings were fuelled by the increased need to prepare and worry about the possible damages. The difficulty of combining reindeer herding and the wolf population was recognised in all respondent groups. The general wish was that the wolf population could be more evenly distributed across the country. However, people in rural areas outside of eastern Finland were not enthusiastic about maintaining an increasing wolf population.

Most of the respondents considered the wolf population in Finland to be too high. People country-wide hoped that the population could be managed by permit-based hunting. There were also calls to take the social effects of a larger wolf population into account in population management. Reindeer herders and people who owned hunting dogs were most against wolves. Several conservation organisations and environmental authorities wished to increase the number of wolves and they did not accept hunting as a means of population management. Instead, they considered increasing wolf awareness and affecting people's attitudes to be the best way to promote the coexistence of humans and wolves.

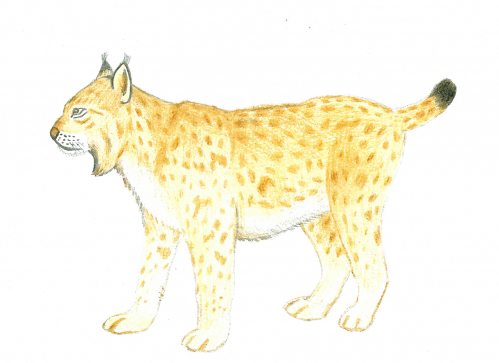

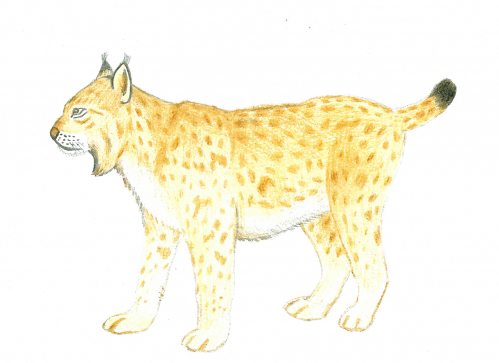

Lynx

The lynx was nearly eradicated from Finland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The population has been recovering since the 1970s and today we have a robust lynx population in the country. The EU's Habitats Directive changed Finnish hunting and conservation legislation to make the lynx a fully protected game animal. The strong growth of the lynx population and its spreading to new areas has elicited a wide variety of comments from Finns. In areas where the lynx population is densest, the discourse has also taken on negative tones.

The survey conducted as part of the drafting process of Finland's lynx population management plan indicated that people have divided attitudes toward the animal. On the one hand, the lynx is considered a valuable game animal that poses no danger to humans. On the other hand the lynx does interfere with game management work and kills other game animals, and on occasion it can also come near populated areas and cause harm to domestic animals or dogs. As the most important methods of promoting the coexistence of humans and lynxes, the respondents identified population management, flexible hunting of troublesome specimens and the development of the compensation system for lynx damages (especially the removal of the system's own-risk deductible).

Especially hunters, kennel people and the representatives of agriculture and forestry were in favour of reducing the number of lynxes. Nearly all regional and national respondent groups were unanimous that population management efforts should focus on high-density lynx areas. In other words, people hoped for a reduction in the number of lynxes in areas where lynx population density and birth rate were highest. Increasing the population was primarily on the agenda of different nature and wildlife conservation organisations. The respondents considered lynx research, improving population estimation methods and increasing lynx awareness to be important.

Large carnivores and people

The resurgence of large carnivores, especially the return of the wolf, has affected people's lives in many ways. The threat of damages caused by large carnivores breeds insecurity and fear. People must pay more attention to protecting their domestic animals. Wolf fences are a thing people will have to get used to. Farmers have had to restrict keeping production animals outside because protecting them during the pasture season may be expensive or even impossible, while at the same time they still have to fulfil the obligations for grazing and outdoor husbandry set by EU legislation.

When large carnivores take pets and domestic animals from people's yards, the predators hit too close to home and their actions are considered an affront to people's ideas of justice and the protection of property. In 2010, bears were seen eating apples in people's yards in North Karelia. This behaviour was speculated to be a result of a bad berry crop and a plentiful apple crop. However, losing a pet or some other domestic animal in one's own yard is a harder pill to swallow than losing a few apples.

Wolf attacks on dogs are a significant problem. There are two reasons why wolves attack dogs: they see dogs as prey animals or they see them as competitors. Radio tracking data collected from six wolf territories indicates a strong individual tendency to attack dogs. Why some wolves decide to enter people's yards may be explained by the wolf taking advantage of a readily accessible food source. Wolves that kill dogs near houses tend to be loners, while attacks on dogs in hunting situations often involve two or more wolves. Protecting dogs during hunts has proven especially difficult.

The return of large carnivores has also created a new sense of community by providing a shared topic of discussion through which people have been able to address broader questions of nature conservation, politics and the transfer of information between authorities and locals.